Um artigo de um jornal português sobre a norma de Leasing.

A IFRS 16 – Locações entrou em vigor a 1 de janeiro de 2019 e teve os seus reflexos na publicação das contas das empresas no primeiro trimestre do ano. Segundo alguns analistas o objetivo da norma não foi totalmente atingido. Qual a razão para que tal tenha acontecido?

A IFRS 16 requere que os locatários contabilizem todas as locações (“operacionais” e “financeiras) com base num modelo único de reconhecimento no balanço. Assim, na data de início da locação, o locatário reconhece a responsabilidade relacionada com os pagamentos da locação e o ativo que representa o direito a usar o bem subjacente (ROU), durante o período da locação.

Simultaneamente, é reconhecido o custo do juro sobre o passivo da locação e a respetiva amortização do ROU. O objetivo pretendido com a norma seria permitir a comparabilidade: i) das demonstrações financeiras através do registo em balanço de todos os ativos e passivos das locações, independentemente da forma de detenção dos ativos e do seu financiamento; e ii) dos indicadores de performance das empresas (KPI’s).

Da análise das contas do primeiro trimestre das principais operadoras de telecomunicações europeias, pode concluir-se que os maiores impactos da aplicação da referida norma, resultam do registo em balanço dos contratos de arrendamento de infraestruturas (sites) de rede móvel e rede fixa, lojas, edifícios, data centres e da apresentação em resultados da amortização do ROU e dos juros do passivo da locação. Simultaneamente, verifica-se que alguns KPI’s anteriormente usados para a avaliação da performance das empresas e acompanhados pelos stakeholders, foram agora significativamente alterados, dificultando a comparabilidade das empresas do setor, no que se refere à análise do grau de alavancagem e da avaliação das empresas. Como consequência e exemplo, algumas empresas passaram a apresentar o EBITDA AL (EBITDA After Leases), um novo KPI que difere significativamente do atual EBITDA, agora sem os gastos de arrendamentos e juros, ou seja, de montante significativamente superior ao EBITDA AL. Será o início do regresso ao passado e dar-se-á a substituição deste KPI pelo Cash Flow?

Apesar das Normas Internacionais de Contabilidade pretenderem a harmonização das informações financeiras apresentadas pelos emissores de valores mobiliários na União Europeia e garantir uma maior transparência e comparabilidade, é necessário a definição de um modelo “único” de divulgação das contas ao mercado e dos KPI’s apresentados, de modo a que uma nova norma, como a IFRS16, não prejudique a comparabilidade das empresas do setor.

Jornal Econômico (Portugal) - Jessica Pereira

12 julho 2019

11 julho 2019

Econometria é uma fraude

Grande boa parte dos modelos econométricos são inúteis. Vou elencar os motivos abaixo:

1) Em variáveis econômicas uma única observação em 10.000, ou seja, um único dia em 40 anos, pode explicar a maior parte da "curtose", a medida padrão de momento finito de caudas pesadas.

2) Para o mercado de ações dos EUA, um único dia, o crash de 1987, determinou 80% da curtose para o período entre 1952 e 2008. O mesmo problema ocorre com juros, taxa câmbio, commodities e outras variáveis econômicas e financeiras.

3) O problema não é apenas que os dados tenham caudas pesadas, algo que as pessoas sabem,

mas que não é possível determinar "caudas pesadas" usando métodos padrões. Isso implica que as ferramentas usadas pelos economistas baseadas na norma L2, ou seja variáveis elevadas ao quadrado, como desvio-padrão, variância, correlação, regressão não têm validade científica. A variância dos quadrados é análogo ao quarto momento. Além disso, p-valor não tem validade com variáveis econômicas e financeiras.

4) Os resultados da maioria dos trabalhos em economia são baseados nesses métodos estatísticos padrões .Portanto, não é esperado que esses estudos sejam replicados, e eles efetivamente não o fazem. Além disso, essas ferramentas incentivam a tomada de riscos não desejados.

5) Aí você pode se perguntar porque muita gente (acadêmicos e economistas) continua a usar métodos econométricos? Econometria captura coisas comuns e mascara efeitos de ordem superior, que são mais importantes. Como falências não são tão freqüentes, eventos extremos não aparecem em dados, então o pesquisador acadêmico parece inteligente na maioria das vezes, enquanto estão na verdade fundamentalmente errados.

6) A lei dos grandes números funciona bem devagar no mundo real, isso quando funciona.

7) A média da distribuição raramente corresponderá à média amostral, particularmente se

a distribuição tem assimetria;

8) Desvio-padrão e variância não podem ser usados em economia e finanças.

9) Beta, razão de Sharpe e outras métricas não são informativas.

10) Regressão Linear não funciona. O Teorema de Gauss-Markov falha, pois só é possível usá-lo quando a amostra é infinita. No mundo real, a amostra é finita. Ou seja, o mundo real é pré-assintótico.

Fonte: Nassim Nicholas Taleb. Errors, robustness, and the fourth quadrant. International

Journal of Forecasting, 25(4):744–759, 2009.

Data Science: a nova astrologia

I’ve spent most of the last six years playing around with data and drawing insights from it (a lot of those insights have been published in Mint). A lot of work that I’ve done can fall under the (rather large) umbrella of “data science", and some of it can be classified as “machine learning". Over the last couple of years, though, I’ve been rather disappointed by what goes on in the name of data science.

Stripped to its bare essentials, machine learning is an exercise in pattern recognition. Given a set of inputs and outputs, the system tunes a set of parameters in a mathematical formula such that the outputs can be predicted with as much accuracy as possible given the inputs (I’m massively oversimplifying here, but this captures sufficient essence for this discussion).

One big advantage with machine learning is that algorithms can sometimes recognize patterns that are not easily visible to the human eye. The most spectacular application of this has been in the field of medical imaging, where time and again algorithms have been shown to outperform human experts while analysing images.

In February last year, a team of researchers from Stanford University showed that a deep learning algorithm they had built performed on par against a team of expert doctors in detecting skin cancer. In July, another team from Stanford built an algorithm to detect heart arrhythmia by analysing electrocardiograms, and showed that it outperformed the average cardiologist. More recently, algorithms to detect pneumonia and breast cancer have been shown to perform better than expert doctors.

The way all these algorithms perform is similar—fed with large sets of images that contain both positive and negative cases of the condition to be detected, they calibrate parameters of a mathematical formula so that patterns that lead to positive and negative cases can be distinguished. Then, when fed with new images, they apply these formulae with the calibrated parameters in order to classify those images.

While applications such as medical imaging might make us believe that machine learning might take over the world, we should keep in mind that left to themselves, machines can go wrong spectacularly. In 2015, for example, Google got into trouble when it tagged photos containing a black woman as “gorillas".

Google admitted the mistake, and that the classification was “unacceptable" but it appears that its engineers couldn’t do much to prevent such classification. Last month, The Guardian reported that Google had gotten around this problem by removing tags such as “gorilla", “chimpanzee" and “monkey" from its database.

The advantage of machine learning—that it can pick up patterns that are not apparent to humans—can be its undoing as well. The gorilla problem aside, the problem with identifying patterns that are not apparent or intuitive to humans is that meaningless patterns can get picked up and amplified as well. In the statistics world, this is known as “spurious correlations".

And as we deal with larger and larger data sets, the possibility of such spurious correlations appearing out of sheer randomness increases. Nassim Nicholas Taleb, author of Fooled by Randomness and The Black Swan had written in 2013 about how “big data" would lead to “big errors".

We are seeing this with modern machine learning algorithms that rely on lots of data as well. For example, a team of researchers from New York University showed that algorithms detecting road signs can be fooled by simply inserting an additional set of training images with an obscure pattern in the corner. More importantly, they showed that a malicious adversary could choose these additional images carefully in a way that the misclassification wouldn’t be apparent when the model was being trained.

Traditionally, the most common method to get around spurious correlations has been for the statistician (or data scientist) to inspect their models and to make sure that they make “intuitive sense". In other words, the models are allowed to find patterns and then a domain expert validates those patterns. In case the patterns don’t make sense, data scientists have tweaked their models in a way that they give more meaningful results.

The other way statisticians have approached the problem is to pick models that are most appropriate for the data at hand. Different mathematical models are adept at detecting patterns in different kinds of data, and picking the right algorithm for the data ensures that spurious pattern detection is minimized.

The problem with modern machine learning algorithms, however, is that the models are hard to inspect and make sense of. It isn’t possible to look at the calibrated parameters of a deep learning system, for example, to see whether the patterns it detects make sense. In fact, “explainability" of artificial intelligence algorithms has become a major topic of interest among researchers.

Given the difficulty of explaining the models, the average data scientist proceeds to use the algorithms as black boxes. Moreover, determining the right model for a given data set is more of an art than science, and involves the process of visually inspecting the data and understanding the maths behind the models.

With standardized packages being available to do the maths, and in a “cheap" manner (a Python package called Scikit Learnallows data scientists to implement just about any machine learning model using three very similar looking lines of code), data scientists have gotten around this “problem".

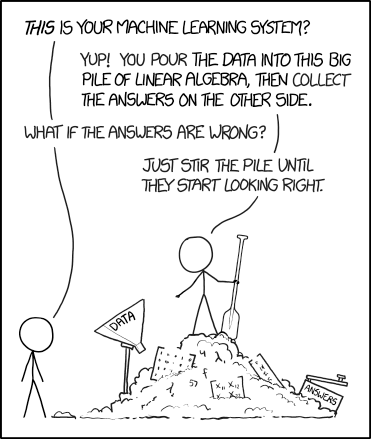

The way a large number of data scientists approach a problem is to take a data set and then apply all possible machine learning methods on it. They then accept the model that gives the best results on the data set at hand. No attempt is made to understand why the given inputs lead to the output, or if the patterns make “physical sense". As this XKCD strip puts it, this is akin to stirring a pile of answers till they start looking right.

And this is not very different from the way astrology works. There, we have a a bunch of predictor variables (position of different “planets" in various parts of the “sky") and observed variables (whether some disaster happened or not, in most cases). And then some of our ancients did some data analysis on this, trying to identify combinations of predictors that predicted the output (unfortunately, they didn’t have the power of statistics or computers, so in that sense the models were limited). And then they simply accepted the outputs, without challenging why it makes sense that the position of Jupiter at the time of wedding affects how someone’s marriage would go.

Armed with this analysis, I brought up the topic of astrology and data science again recently, telling my wife that “after careful analysis I admit that astrology is the oldest form of data science".

“That’s not what I said," Priyanka countered. “I said that data science is new-age astrology, and not the other way round."

Fonte: aqui

Fasb aprendendo a simplificar

O Fasb está convidando as pessoas a comentarem uma proposta de alteração na norma de goodwill. A norma atual seria altamente complexa, onde a relação custo-benefício da informação é desfavorável para a empresa.

Um aspecto interessante destacada por Jeff Drew em um texto para o Journal of Accountancy é papel do Private Company Council. Esta entidade foi criada para adaptar as normas do Fasb para as empresas de capital fechado dos Estados Unidos. Em muitos casos, o PCC indica quais normas devem ser seguidas, quais que não devem ser seguidas e, em certos casos, um tratamento alternativo e mais simplificado para a norma.

Parece que no caso do goodwill, o tratamento proposto pelo PCC reduziu custo e complexidade sem perda de qualidade da informação. Isto significa dizer que o PCC funcionou como um laboratório para melhorar a qualidade da norma e a relação custo-benefício da informação.

No Brasil não temos uma entidade similar. Em certos casos, o CFC faz um pouco este papel, ao propor uma norma para empresas de pequeno porte. Mesmo no Iasb isto termina por não acontecer.

Um aspecto interessante destacada por Jeff Drew em um texto para o Journal of Accountancy é papel do Private Company Council. Esta entidade foi criada para adaptar as normas do Fasb para as empresas de capital fechado dos Estados Unidos. Em muitos casos, o PCC indica quais normas devem ser seguidas, quais que não devem ser seguidas e, em certos casos, um tratamento alternativo e mais simplificado para a norma.

Parece que no caso do goodwill, o tratamento proposto pelo PCC reduziu custo e complexidade sem perda de qualidade da informação. Isto significa dizer que o PCC funcionou como um laboratório para melhorar a qualidade da norma e a relação custo-benefício da informação.

No Brasil não temos uma entidade similar. Em certos casos, o CFC faz um pouco este papel, ao propor uma norma para empresas de pequeno porte. Mesmo no Iasb isto termina por não acontecer.

Padrão na Contabilidade Forense

O AICPA divulgou um documento denominado Statement on Standards for Forensic Services No. 1, abrangendo litígio e investigação. Com quatro páginas e 11 itens, o documento traça aspectos gerais sobre a área. É válido para profissionais dos EUA que atuam na área.

Assinar:

Postagens (Atom)