22 julho 2017

21 julho 2017

Inteligência artificial não acabará com Wall Street

For all the hype, applying AI to investment still has a few serious problems

Artificial intelligence and machine learning are the buzzwords in automated investment. But for all the hype, applying AI to investment still has its problems.

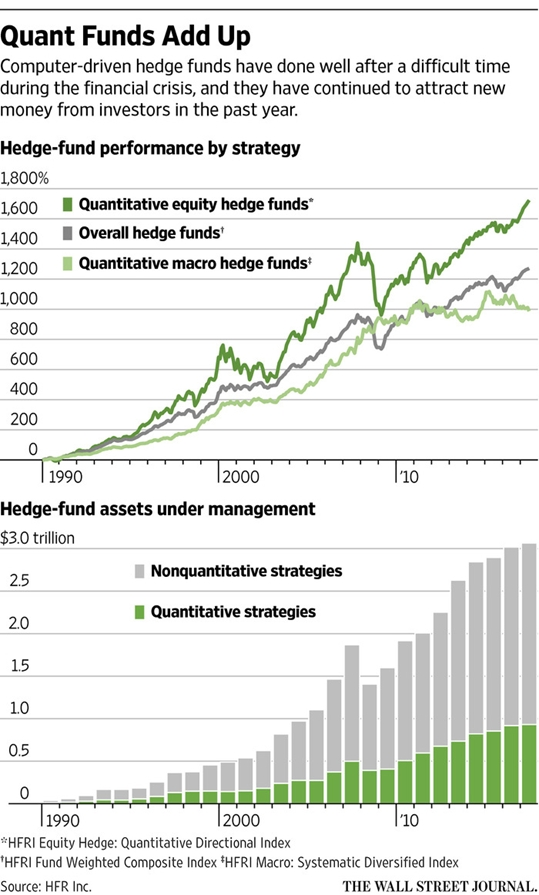

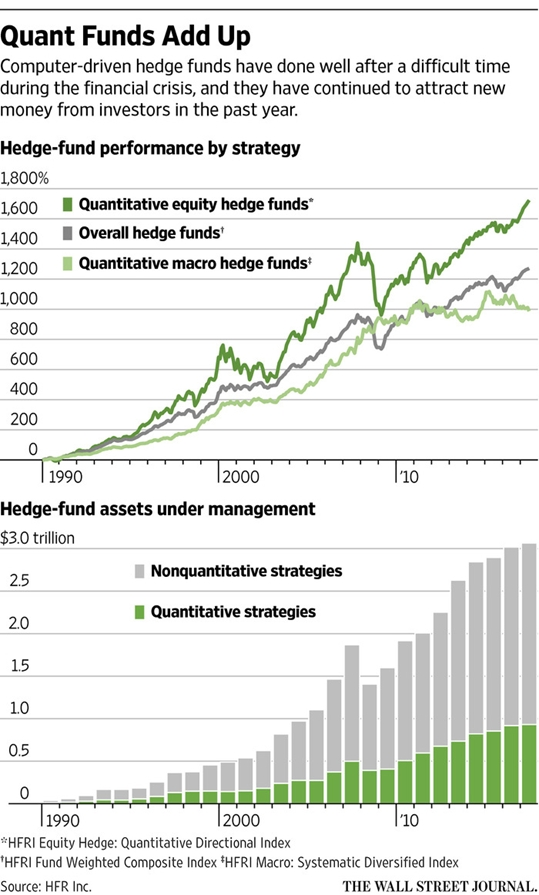

Ten years ago, computer-driven traders pulled the plug after their algorithms ran amok, leading to billions in losses and the eventual closure of Goldman Sachs ’s flagship quantitative fund.

A decade on, artificial intelligence and machine learning are the buzzwords in automated investment. But for all the hype, applying AI to investment has three serious problems: it works too well, it is often impossible to understand, and it only knows about recent history. Worse, it will be self-defeating if it proves popular, as algorithms face off against each other in the market.

Machine-learning systems are now really good at spotting patterns. Unfortunately, computers are just too good, and frequently find patterns that aren’t really there.Michael Kollo, chief strategist at Axa IM Rosenberg Equities, points to the neural network—a type of AI loosely modeled on brains—developed by three University of Washington researchers to distinguish between pictures of wolves and dogs by associating wolves with snow.

“It can easily identify something of an intransigent nature and learn one rule from it,” he says. Train an AI on the last 35 years of markets, and it might well develop a single simple rule: buy bonds. With 10-year Treasury yields down from 13.7% in July 1982 to 2.31% on Monday, it worked beautifully in hindsight—but yields can’t possibly fall that much again in the next 35 years.

In the industry, spotting patterns that don’t repeat is known as “overfitting”—picking up on the irrelevant snow in the picture of a wolf, or chance patterns in past stock prices that bear no relation to the future.

David Harding, founder of hedge fund Winton Group, says finding ways to avoid such fake patterns is at the core of computer-driven investment.

“Avoiding overfitting is a state of mind,” he says. “It’s the same thing as avoiding wishful thinking.”

Anthony Ledford, chief scientist at quant fund Man AHL, says more advanced machine learning systems sometimes prove less useful, too. “The more complicated your model the better it is at explaining the data you use for the training and the less good it is about explaining the data in the future,” he says. A model needs to accept that much that goes on in markets is meaningless noise, and try to pick out broader signals, even if it leaves some moves in past data unexplained.

Anthony Ledford, chief scientist at quant fund Man AHL, says more advanced machine learning systems sometimes prove less useful, too. “The more complicated your model the better it is at explaining the data you use for the training and the less good it is about explaining the data in the future,” he says. A model needs to accept that much that goes on in markets is meaningless noise, and try to pick out broader signals, even if it leaves some moves in past data unexplained.

Many quantitative investors try to avoid overfitting by insisting that any rule they adopt should have an economic or behavioral rationale. If the computer finds that every third Wednesday when it rains in Kansas the stocks of oil companies listed in Paris go up, betting on it happening in future would be no more than a leap of faith.

Unfortunately, explaining why a system with thousands of inputs made a decision can be all but impossible—and is such a serious problem that America’s defense research agency is financing a program to try to produce AI which explains itself.

The lack of transparency means the most advanced systems tend to be run on a tentative basis, with only a small amount of money or with human oversight of the recommendations.

Charles Ellis is typical. He joined Mediolanum Asset Management in Dublin in November to develop machine learning systems, with the first up and running providing recommendations for sectors. Given 20 years of data on 1,500 variables related to U.S. stocks, it uses a machine learning system known as random forest regression to try to avoid overfitting, and early results are good, he says. It is being used only for a small part of the $20 billion portfolio, with final decisions still made by fund managers. A second system designed to try to predict the economic cycle is currently bullish.

The drawback of the random forest method is that it is hard to understand why the computer reached any particular decision.

“It’s a little bit of a black box in that you don’t know why [the input]’s having that effect,” he says.

Mr. Kollo says it will be hard to avoid shutting down a system when it loses money if it isn’t properly understood.

“All things go wrong eventually, every algorithm has a bad day,” he says. “The difference between those that survive and don’t is those that can explain what they do.”

Some investors don’t care about the lack of transparency. Jeffrey Tarrant, whose Protégé Partners invests in hedge funds, says it “doesn’t bother me at all.” He’s invested in six funds which use AI methods—typically combined with unusual data sources—and whose managers come from nonstandard backgrounds. He estimates there are 75 funds which say they use AI, but thinks only 25 really do.

Investors who have long managed money using computers are scornful of the latest fashion for AI.

“Thirty years of being treated like an idiot for saying you can manage money with computers, and now they come along and say you can manage money with computers,” scoffs Mr. Harding at Winton.

His application of a form of machine learning to moving averages of futures prices helped him become a billionaire. His team treats machine learning as just another statistical technique to spot market anomalies.

Sushil Wadhwani used machine learning when head of systems trading at hedge fund Tudor two decades ago, and now runs his own automated fund using machine learning—but overrides the systems occasionally. In 2008 he turned off the European bond analysis because it had learned that spreads between the best and worst eurozone bonds didn’t depend on economic fundamentals, after years of evidence. As the banking system imploded, he knew this no longer applied.

“It would be very difficult for a machine to learn that unless it knew it should be looking at the 1930s,” he says.

High-frequency systems may get enough examples of changing trading regimes to run on their own, but can’t deploy much capital. Applying machine learning to longer-term investment is tricky when many of the new data sets being deployed only go back a decade or two. Computers with no knowledge of history are doomed to repeat its mistakes.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning are the buzzwords in automated investment. But for all the hype, applying AI to investment still has its problems.

Ten years ago, computer-driven traders pulled the plug after their algorithms ran amok, leading to billions in losses and the eventual closure of Goldman Sachs ’s flagship quantitative fund.

A decade on, artificial intelligence and machine learning are the buzzwords in automated investment. But for all the hype, applying AI to investment has three serious problems: it works too well, it is often impossible to understand, and it only knows about recent history. Worse, it will be self-defeating if it proves popular, as algorithms face off against each other in the market.

Machine-learning systems are now really good at spotting patterns. Unfortunately, computers are just too good, and frequently find patterns that aren’t really there.Michael Kollo, chief strategist at Axa IM Rosenberg Equities, points to the neural network—a type of AI loosely modeled on brains—developed by three University of Washington researchers to distinguish between pictures of wolves and dogs by associating wolves with snow.

“It can easily identify something of an intransigent nature and learn one rule from it,” he says. Train an AI on the last 35 years of markets, and it might well develop a single simple rule: buy bonds. With 10-year Treasury yields down from 13.7% in July 1982 to 2.31% on Monday, it worked beautifully in hindsight—but yields can’t possibly fall that much again in the next 35 years.

In the industry, spotting patterns that don’t repeat is known as “overfitting”—picking up on the irrelevant snow in the picture of a wolf, or chance patterns in past stock prices that bear no relation to the future.

David Harding, founder of hedge fund Winton Group, says finding ways to avoid such fake patterns is at the core of computer-driven investment.

“Avoiding overfitting is a state of mind,” he says. “It’s the same thing as avoiding wishful thinking.”

Anthony Ledford, chief scientist at quant fund Man AHL, says more advanced machine learning systems sometimes prove less useful, too. “The more complicated your model the better it is at explaining the data you use for the training and the less good it is about explaining the data in the future,” he says. A model needs to accept that much that goes on in markets is meaningless noise, and try to pick out broader signals, even if it leaves some moves in past data unexplained.

Anthony Ledford, chief scientist at quant fund Man AHL, says more advanced machine learning systems sometimes prove less useful, too. “The more complicated your model the better it is at explaining the data you use for the training and the less good it is about explaining the data in the future,” he says. A model needs to accept that much that goes on in markets is meaningless noise, and try to pick out broader signals, even if it leaves some moves in past data unexplained.Many quantitative investors try to avoid overfitting by insisting that any rule they adopt should have an economic or behavioral rationale. If the computer finds that every third Wednesday when it rains in Kansas the stocks of oil companies listed in Paris go up, betting on it happening in future would be no more than a leap of faith.

Unfortunately, explaining why a system with thousands of inputs made a decision can be all but impossible—and is such a serious problem that America’s defense research agency is financing a program to try to produce AI which explains itself.

The lack of transparency means the most advanced systems tend to be run on a tentative basis, with only a small amount of money or with human oversight of the recommendations.

Charles Ellis is typical. He joined Mediolanum Asset Management in Dublin in November to develop machine learning systems, with the first up and running providing recommendations for sectors. Given 20 years of data on 1,500 variables related to U.S. stocks, it uses a machine learning system known as random forest regression to try to avoid overfitting, and early results are good, he says. It is being used only for a small part of the $20 billion portfolio, with final decisions still made by fund managers. A second system designed to try to predict the economic cycle is currently bullish.

The drawback of the random forest method is that it is hard to understand why the computer reached any particular decision.

“It’s a little bit of a black box in that you don’t know why [the input]’s having that effect,” he says.

Mr. Kollo says it will be hard to avoid shutting down a system when it loses money if it isn’t properly understood.

“All things go wrong eventually, every algorithm has a bad day,” he says. “The difference between those that survive and don’t is those that can explain what they do.”

Some investors don’t care about the lack of transparency. Jeffrey Tarrant, whose Protégé Partners invests in hedge funds, says it “doesn’t bother me at all.” He’s invested in six funds which use AI methods—typically combined with unusual data sources—and whose managers come from nonstandard backgrounds. He estimates there are 75 funds which say they use AI, but thinks only 25 really do.

Investors who have long managed money using computers are scornful of the latest fashion for AI.

“Thirty years of being treated like an idiot for saying you can manage money with computers, and now they come along and say you can manage money with computers,” scoffs Mr. Harding at Winton.

His application of a form of machine learning to moving averages of futures prices helped him become a billionaire. His team treats machine learning as just another statistical technique to spot market anomalies.

Sushil Wadhwani used machine learning when head of systems trading at hedge fund Tudor two decades ago, and now runs his own automated fund using machine learning—but overrides the systems occasionally. In 2008 he turned off the European bond analysis because it had learned that spreads between the best and worst eurozone bonds didn’t depend on economic fundamentals, after years of evidence. As the banking system imploded, he knew this no longer applied.

“It would be very difficult for a machine to learn that unless it knew it should be looking at the 1930s,” he says.

High-frequency systems may get enough examples of changing trading regimes to run on their own, but can’t deploy much capital. Applying machine learning to longer-term investment is tricky when many of the new data sets being deployed only go back a decade or two. Computers with no knowledge of history are doomed to repeat its mistakes.

20 julho 2017

Chega de aumentar impostos!

Não é difícil entender por que o governo se viu obrigado a aumentar os impostos sobre combustíveis. Basta fazer as contas para perceber que o cumprimento da meta fiscal, um déficit de RS 139 bilhões até dezembro, se tornou inviável.

A arrecadação subiu pouco no primeiro semestre deste ano, — 0,8%, para RS 648,6 bilhões. A causa desse crescimento foram receitas extraordinárias, como royalties do petróleo, que andavam em baixa no ano passado. Descontadas elas, houve queda de 0,2%. Apenas em resultado disso, pode haver um buraco fiscal de até RS 18 bilhões na meta.

Mas os problemas da Receita não param por aí. O Parlamento resiste a reonerar a folha de pagamento de empresas beneficiadas durante o governo Dilma, abrindo um buraco de mais RS 2 bilhões. O atraso na privatização de estatais, como o Instituto de Resseguros do Brasil (IRB), abrirá outro de RS 7 bilhões.

A segunda fase do programa de repatriação de recursos está aquém do esperado: até agora, a Receita recebeu apenas RS 800 milhões de 836 contribuintes (o prazo se esgota em 15 dias), ante a expectativa inicial de RS 6,7 bilhões — mais um buraco, de RS 5,9 bilhões.

E, assim, de buraco em buraco, o governo vai abrindo um rombo gigantesco no Orçamento, que precisa ser coberto de alguma forma, sob pena de pôr em xeque a credibilidade da equipe econômica. Foram levantados apenas RS 12 bilhões com receitas de precatórios atrasados — valor insuficiente para cumprir a meta fiscal.

O difícil é entender por que, para tapar o rombo, é preciso aumentar combustíveis, quando o Congresso está prestes a aprovar, por meio da Medida Provisória 783, um perdão para as dívidas das empresas que as dispensa de pagar 99% dos juros e multas relativos a atrasos nos impostos. É a segunda MP desfigurada na Câmara para atender aos interesses dos devedores. A primeira foi a 766, em março.

A expectativa inicial era arrecadar RS 13,3 bilhões este ano com os pagamentos atrasados. Na forma como a MP passou na Comissão Mista do Congresso, serão apenas RS 420 milhões. Uma reportagem do jornal “O Estado de S.Paulo” revelou ontem que parlamentares, cujas empresas devem RS 533 milhões, também serão beneficiados.

Fora os parlamentares, outro grupo político beneficiado pelo governo são os funcionários públicos. No ano passado, o Executivo autorizou reajustes de 10,8% em dois anos nos salários do funcionalismo — para algumas carreiras, de até 53%. Neste ano, houve equiparação de outras carreiras não contempladas, com aumentos de vencimentos que chegam a 28% nos próximos quatro anos.

Eis, em síntese, a raiz das voltas que o Brasil vive a dar ao redor do abismo fiscal: quem tem poder ou exerce pressão — empresas, sindicatos do funcionalismo e, naturalmente, políticos — garante o seu. Para o cidadão comum — que não sonega, não tem apartamento não-declarado em Miami, não desfruta os privilégios legais do funcionalismo, nem ocupa assento no Congresso —, nada resta senão mais uma tunga no bolso.

O aumento de imposto, sobretudo no combustível, se refletirá nos índices inflacionários, além de ampliar a já assombrosa carga tributária que emperra a produtividade da economia brasileira e faz dos produtos vendidos os mais caros do mundo. Mesmo que seja um aumento pequeno, viola princípios pelos quais todo brasileiro deveria lutar, como o enxugamento do Estado, o fim do clientelismo e o corte de gastos públicos.

É intolerável que paguemos mais do que já pagamos. Como o Tea Party americano, a independência do Brasil também nasceu numa revolta contra impostos, a Inconfidência Mineira. Está na hora de fazer reviver os ideais dos inconfidentes, contra a derrama sorrateira que o governo não cessa de praticar contra a sociedade. Chega de impostos!

A arrecadação subiu pouco no primeiro semestre deste ano, — 0,8%, para RS 648,6 bilhões. A causa desse crescimento foram receitas extraordinárias, como royalties do petróleo, que andavam em baixa no ano passado. Descontadas elas, houve queda de 0,2%. Apenas em resultado disso, pode haver um buraco fiscal de até RS 18 bilhões na meta.

Mas os problemas da Receita não param por aí. O Parlamento resiste a reonerar a folha de pagamento de empresas beneficiadas durante o governo Dilma, abrindo um buraco de mais RS 2 bilhões. O atraso na privatização de estatais, como o Instituto de Resseguros do Brasil (IRB), abrirá outro de RS 7 bilhões.

A segunda fase do programa de repatriação de recursos está aquém do esperado: até agora, a Receita recebeu apenas RS 800 milhões de 836 contribuintes (o prazo se esgota em 15 dias), ante a expectativa inicial de RS 6,7 bilhões — mais um buraco, de RS 5,9 bilhões.

E, assim, de buraco em buraco, o governo vai abrindo um rombo gigantesco no Orçamento, que precisa ser coberto de alguma forma, sob pena de pôr em xeque a credibilidade da equipe econômica. Foram levantados apenas RS 12 bilhões com receitas de precatórios atrasados — valor insuficiente para cumprir a meta fiscal.

O difícil é entender por que, para tapar o rombo, é preciso aumentar combustíveis, quando o Congresso está prestes a aprovar, por meio da Medida Provisória 783, um perdão para as dívidas das empresas que as dispensa de pagar 99% dos juros e multas relativos a atrasos nos impostos. É a segunda MP desfigurada na Câmara para atender aos interesses dos devedores. A primeira foi a 766, em março.

A expectativa inicial era arrecadar RS 13,3 bilhões este ano com os pagamentos atrasados. Na forma como a MP passou na Comissão Mista do Congresso, serão apenas RS 420 milhões. Uma reportagem do jornal “O Estado de S.Paulo” revelou ontem que parlamentares, cujas empresas devem RS 533 milhões, também serão beneficiados.

Fora os parlamentares, outro grupo político beneficiado pelo governo são os funcionários públicos. No ano passado, o Executivo autorizou reajustes de 10,8% em dois anos nos salários do funcionalismo — para algumas carreiras, de até 53%. Neste ano, houve equiparação de outras carreiras não contempladas, com aumentos de vencimentos que chegam a 28% nos próximos quatro anos.

Eis, em síntese, a raiz das voltas que o Brasil vive a dar ao redor do abismo fiscal: quem tem poder ou exerce pressão — empresas, sindicatos do funcionalismo e, naturalmente, políticos — garante o seu. Para o cidadão comum — que não sonega, não tem apartamento não-declarado em Miami, não desfruta os privilégios legais do funcionalismo, nem ocupa assento no Congresso —, nada resta senão mais uma tunga no bolso.

O aumento de imposto, sobretudo no combustível, se refletirá nos índices inflacionários, além de ampliar a já assombrosa carga tributária que emperra a produtividade da economia brasileira e faz dos produtos vendidos os mais caros do mundo. Mesmo que seja um aumento pequeno, viola princípios pelos quais todo brasileiro deveria lutar, como o enxugamento do Estado, o fim do clientelismo e o corte de gastos públicos.

É intolerável que paguemos mais do que já pagamos. Como o Tea Party americano, a independência do Brasil também nasceu numa revolta contra impostos, a Inconfidência Mineira. Está na hora de fazer reviver os ideais dos inconfidentes, contra a derrama sorrateira que o governo não cessa de praticar contra a sociedade. Chega de impostos!

Fonte: Helio Gurovitz

Assinar:

Postagens (Atom)